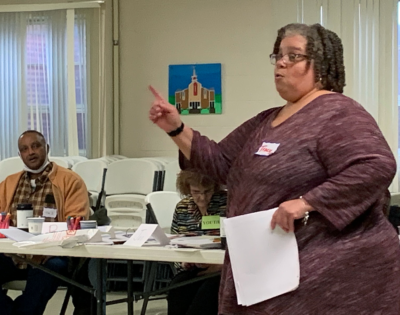

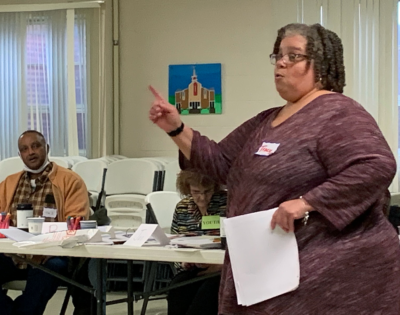

Tracy Anderson

It’s a saying that stuck with Tracy Anderson when she worked with the elderly in Athens. As she said, “See you tomorrow,” at the end of the day, she often heard in response, “God willing, and the creek don’t rise.” The saying seemed to acknowledge their lack of power to control their lives while also demonstrating an acceptance, and even joy, in whatever comes next. Time and again, she marveled at the ability of these older and often impoverished clients to get on with life while also realizing they did not have much of it left.

The sentiment might also apply well to her own life because it suggests two things that have been central to her: Learning to recognize and appreciate what she has while helping others get the most they can from their lives.

Now the Assistant Director of the Center for Family Research at UGA, Anderson supports ongoing research projects, but she is instrumental in helping the work of the center get disseminated in ways that directly help families in Georgia and around the nation. While this application of research has become a central theme of her career, working at a UGA research center was not in her earliest plans.

me see how protected I had been

After graduating from UGA with a bachelor’s degree in health promotion, Anderson’s first job was on the front lines of mental health services in Macon, helping those with serious substance addictions and mental health issues at a behavioral health center. For the self-described “church kid,” it was an eye-opening experience.

“It was hard, heartbreaking work,” she said of watching clients with mental health and addiction issues struggle. But she persevered for four years, helping some clients succeed in improving their lives while watching others return again and again. The experience opened her eyes to a reality she had not known, and “it really let me see how protected I had been.”

A family foundation

Anderson grew up in a loving, supportive family that met her needs and provided opportunities. But it might not have been that way.

She noticed the difference between her neighborhood and the ones where many of her school friends lived. But it took many more years before she appreciated the difference between the middle-class life she and her two brothers experienced and those of others who had less. The kind of upbringing she had was possible because of “all the work that my parents put in,” she said.

Her father’s father was a sharecropper, and seeing how exploitive the system was, Anderson’s father became active in the civil rights movement while attending college in the 1960s. It was after a meeting at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta that he met the woman who would become Anderson’s mother.

After college, her father served in the Army, fought in Vietnam, and soon after, began a federal job. Her mother took different positions as a teacher, secretary, and in social services, as they moved around some to accommodate her father’s promotions. This combined effort afforded them the middle-class lifestyle she enjoyed growing up.

Anderson’s love and appreciation for her parents is palpable, and it seems to have given her the foundation she needed to seek out meaning and purpose in her own life. Her approach to work and life is rooted in a strong faith, the value of education, love of country, and a recognition that she had advantages growing up that others did not. But it was not until that challenging first job in Macon that the intense drive to help those less fortunate really came into focus.

Wanting better helping skills as well as professional opportunity, this drive eventually brought her back to UGA to pursue a Master of Social Work (MSW) degree. In the process, an internship with an agency in Atlanta led her to believe her gift was working with the elderly. So after receiving her MSW, she found work at the Athens Community Council on Aging (ACCA).

“The opportunity to add value to the end of someone’s life was really beautiful,” she said of her years at ACCA, “though heartbreaking.” But the experience further cemented her purpose in life—making a difference in the lives of others, which would give her own life meaning.

Tending the garden

About 35 years ago, around the time Anderson was entering UGA as a freshman, new research began at the Center for Family Research to better understand the strengths of Black families. Gene Brody, co-director of the center, followed more than 600 families for over a decade and identified caregiving and parenting practices that forecasted doing well in school, having good emotional health, and avoidance of drugs and risky behaviors for youth in the families.

The findings were significant and contributed much to the scientific literature on family development and parenting. But Brody realized the findings could have a direct effect on the development of Black children and their families if those findings were used to encourage families to engage in competence-promoting parenting practices. So the center set about developing what would eventually be known as the Strong African American Families program (SAAF)—a seven-week, community-based workshop for families and youth aged 10 to 14 that builds on the strength of Black families. Prior to this work, “there were no efficacious prevention programs for Black children and youth,” said Brody.

Not long before the center started testing the effectiveness of SAAF (and finding it is very effective), Anderson found an opportunity to join CFR helping with a research project on single mothers. Eventually, she began helping with training and disseminating SAAF.

From the beginning, she “stood out as an extraordinarily mature and thoughtful person,” said CFR Associate Director Anita Brown. When the person who initially coordinated the implementation of the SAAF trial left the university, it was a no-brainer to hand over leadership to Anderson, according to Brown. “She is just so good at organization and her people skills are off the chart.”

About the same time, Brody saw the need for someone to manage the people and operations of CFR more closely—what he called “tending the garden.” Anderson’s organizational and people skills were the perfect match, and she was given the job of assistant director. In the position she manages project coordinators who handle the day-to-day work of finding research participants, running the data collection, and data management of several ongoing research projects. Anderson provides not only oversight, but the emotional support necessary to work through the challenges that arise from this kind of family-level research.

Not long after taking over these responsibilities, Anderson began work on a Ph.D. in adult education at UGA and finished in 2008. Her “Triple Dawg” credential (three UGA degrees) and history make her thoroughly a Georgian scholar, which makes the work of CFR all the more important to her.

These are my people

Anderson’s passion is getting CFR research out to the families and communities where it can help. With nearly 800 facilitators trained in over 50 cities around the country, today Anderson leads the dissemination of SAAF as well as SAAF-Teen.

She finds extra motivation in the dissemination of the SAAF programs and the research projects involved because, as she put it, “these are my people,” referring to many research participants who are from rural Georgia communities. Her mother is from Louisville, Georgia—a small town southwest of Augusta—and there have been research participants from there since the beginning of the SAAF project. It gives her great satisfaction to know that the work being done involves people from communities that she treasures, she said. It offers her a chance to help be a voice for them in research, when necessary, but also a feeling of doing something directly for people in the area from which she hails.

Today, Anderson tends a number of gardens besides CFR, including keeping an eye on her aging parents who live about an hour away and serving as a trustee at her church. Whether in her personal or her professional life, she strives to make a difference based on her appreciation of what she has been given. “The legacy of Tracy’s work,” said Gene Brody, “is that every week in places around the country there are Black youth and their caregivers participating in SAAF and SAAF-T, and those experiences will leave an imprint on a lot of lives.”

It’s a saying that stuck with Tracy Anderson when she worked with the elderly in Athens. As she said, “See you tomorrow,” at the end of the day, she often heard in response, “God willing, and the creek don’t rise.” The saying seemed to acknowledge their lack of power to control their lives while also demonstrating an acceptance, and even joy, in whatever comes next. Time and again, she marveled at the ability of these older and often impoverished clients to get on with life while also realizing they did not have much of it left.

The sentiment might also apply well to her own life because it suggests two things that have been central to her: Learning to recognize and appreciate what she has while helping others get the most they can from their lives.

Now the Assistant Director of the Center for Family Research at UGA, Anderson supports ongoing research projects, but she is instrumental in helping the work of the center get disseminated in ways that directly help families in Georgia and around the nation. While this application of research has become a central theme of her career, working at a UGA research center was not in her earliest plans.

me see how protected I had been

After graduating from UGA with a bachelor’s degree in health promotion, Anderson’s first job was on the front lines of mental health services in Macon, helping those with serious substance addictions and mental health issues at a behavioral health center. For the self-described “church kid,” it was an eye-opening experience.

“It was hard, heartbreaking work,” she said of watching clients with mental health and addiction issues struggle. But she persevered for four years, helping some clients succeed in improving their lives while watching others return again and again. The experience opened her eyes to a reality she had not known, and “it really let me see how protected I had been.”

A family foundation

Anderson grew up in a loving, supportive family that met her needs and provided opportunities. But it might not have been that way.

She noticed the difference between her neighborhood and the ones where many of her school friends lived. But it took many more years before she appreciated the difference between the middle-class life she and her two brothers experienced and those of others who had less. The kind of upbringing she had was possible because of “all the work that my parents put in,” she said.

Her father’s father was a sharecropper, and seeing how exploitive the system was, Anderson’s father became active in the civil rights movement while attending college in the 1960s. It was after a meeting at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta that he met the woman who would become Anderson’s mother.

After college, her father served in the Army, fought in Vietnam, and soon after, began a federal job. Her mother took different positions as a teacher, secretary, and in social services, as they moved around some to accommodate her father’s promotions. This combined effort afforded them the middle-class lifestyle she enjoyed growing up.

Anderson’s love and appreciation for her parents is palpable, and it seems to have given her the foundation she needed to seek out meaning and purpose in her own life. Her approach to work and life is rooted in a strong faith, the value of education, love of country, and a recognition that she had advantages growing up that others did not. But it was not until that challenging first job in Macon that the intense drive to help those less fortunate really came into focus.

Wanting better helping skills as well as professional opportunity, this drive eventually brought her back to UGA to pursue a Master of Social Work (MSW) degree. In the process, an internship with an agency in Atlanta led her to believe her gift was working with the elderly. So after receiving her MSW, she found work at the Athens Community Council on Aging (ACCA).

“The opportunity to add value to the end of someone’s life was really beautiful,” she said of her years at ACCA, “though heartbreaking.” But the experience further cemented her purpose in life—making a difference in the lives of others, which would give her own life meaning.

Tending the garden

About 35 years ago, around the time Anderson was entering UGA as a freshman, new research began at the Center for Family Research to better understand the strengths of Black families. Gene Brody, co-director of the center, followed more than 600 families for over a decade and identified caregiving and parenting practices that forecasted doing well in school, having good emotional health, and avoidance of drugs and risky behaviors for youth in the families.

The findings were significant and contributed much to the scientific literature on family development and parenting. But Brody realized the findings could have a direct effect on the development of Black children and their families if those findings were used to encourage families to engage in competence-promoting parenting practices. So the center set about developing what would eventually be known as the Strong African American Families program (SAAF)—a seven-week, community-based workshop for families and youth aged 10 to 14 that builds on the strength of Black families. Prior to this work, “there were no efficacious prevention programs for Black children and youth,” said Brody.

Not long before the center started testing the effectiveness of SAAF (and finding it is very effective), Anderson found an opportunity to join CFR helping with a research project on single mothers. Eventually, she began helping with training and disseminating SAAF.

From the beginning, she “stood out as an extraordinarily mature and thoughtful person,” said CFR Associate Director Anita Brown. When the person who initially coordinated the implementation of the SAAF trial left the university, it was a no-brainer to hand over leadership to Anderson, according to Brown. “She is just so good at organization and her people skills are off the chart.”

About the same time, Brody saw the need for someone to manage the people and operations of CFR more closely—what he called “tending the garden.” Anderson’s organizational and people skills were the perfect match, and she was given the job of assistant director. In the position she manages project coordinators who handle the day-to-day work of finding research participants, running the data collection, and data management of several ongoing research projects. Anderson provides not only oversight, but the emotional support necessary to work through the challenges that arise from this kind of family-level research.

Not long after taking over these responsibilities, Anderson began work on a Ph.D. in adult education at UGA and finished in 2008. Her “Triple Dawg” credential (three UGA degrees) and history make her thoroughly a Georgian scholar, which makes the work of CFR all the more important to her.

These are my people

Anderson’s passion is getting CFR research out to the families and communities where it can help. With nearly 800 facilitators trained in over 50 cities around the country, today Anderson leads the dissemination of SAAF as well as SAAF-Teen.

She finds extra motivation in the dissemination of the SAAF programs and the research projects involved because, as she put it, “these are my people,” referring to many research participants who are from rural Georgia communities. Her mother is from Louisville, Georgia—a small town southwest of Augusta—and there have been research participants from there since the beginning of the SAAF project. It gives her great satisfaction to know that the work being done involves people from communities that she treasures, she said. It offers her a chance to help be a voice for them in research, when necessary, but also a feeling of doing something directly for people in the area from which she hails.

Today, Anderson tends a number of gardens besides CFR, including keeping an eye on her aging parents who live about an hour away and serving as a trustee at her church. Whether in her personal or her professional life, she strives to make a difference based on her appreciation of what she has been given. “The legacy of Tracy’s work,” said Gene Brody, “is that every week in places around the country there are Black youth and their caregivers participating in SAAF and SAAF-T, and those experiences will leave an imprint on a lot of lives.”