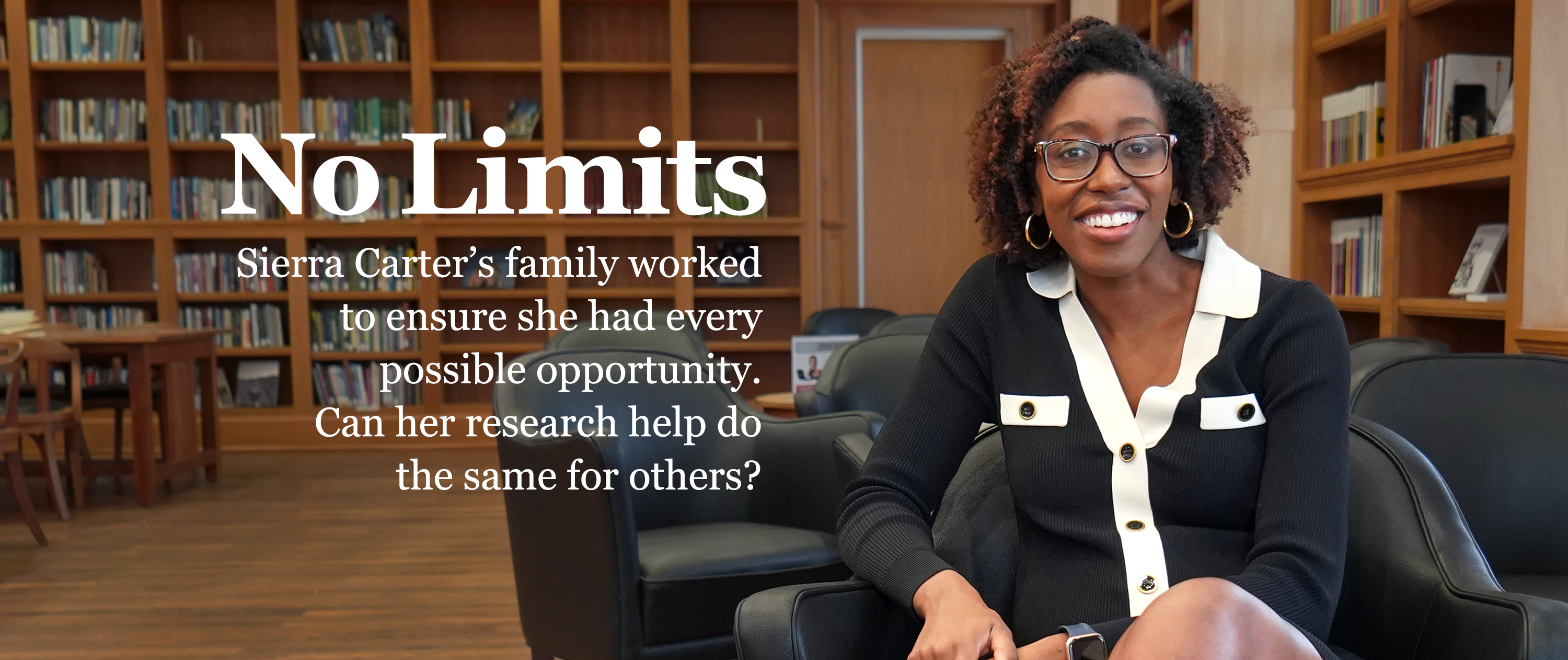

Sierra Carter

the structures of society were not working for them

A component of having opportunity in life is the chance to live a long, healthy one.

“Somebody needs to do something,” Sierra Carter thought to herself during her post-doc at the Grady Trauma Project through Emory University. She was seeing a lot of Black people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and it got her thinking more about how the structures of society were not working for them. The thought helped define and shape her scholarly career. But it was not the first time she was alarmed by how the broader systems were affecting Black Americans.

Growing up in her small southern Virginia town, the chronic illnesses of family, friends, and community members—and not just among the very old—were often present. “Seeing people you know and love not be able to live long and thriving lives was hard to witness,” she says.

But it was not until she interviewed family and community members for a college class that she started connecting the dots and realized the chronic illnesses and early deaths of people around her was not only a part of the community she grew up in but was also a part of other Black communities as well. It led to a startling realization: Black people tended to die younger than those in many other groups.

Fast forward a few years, and Dr. Carter’s recent lecture entitled, “Black people deserve to grow old: Racial trauma, accelerated aging, and the promotion of health-equity related research,” shows that she is trying to do something about the problem. But the college-aged Carter would have been surprised to know she was heading into a life of scholarly work.

They wanted me not to have to work as hard as they did

The push for success

Until heading off to college at UNC Chapel Hill, just over an hour from the home she shared with her parents and older brother, Carter spent her whole life in the same town, in the same house in Axton, Virginia, near the border with North Carolina. The amount of support she had growing up “was ridiculous,” she says. Her parents, aunts, extended family and others pushed and pulled, sometimes behind the scenes and unknown to her, to make sure she and her brother knew they could be and do whatever they dreamed of. Both her parents attended every parent-teacher conference in her life as one simple example of their support and involvement. “They wanted me not to have to work as hard as they did,” Carter explains.

But that support was also wrapped up with some high expectations. For example, she says, “my parents didn’t believe in missing school.” It did not matter if she was sick or whatever. She went (and ended up with a perfect attendance record).

Carter’s father, who coached basketball in recreation and school programs for years, applied his own philosophy to her in that world. He often encouraged her to play in the next, older age group, for instance, and talked about basketball as her path to success—a practical way to pay for college, and then hopefully, into something more than a factory job.

He told Carter and her brother from a young age that, “if you get a scholarship in basketball, I’ll buy you a car,” she says as one of his ways of motivating them to excel.

Sometimes, while her dad was mentoring and coaching the boys and girls at the YMCA on Saturday mornings, some of the older girls would take her away to the library just across the street where she would end up spending the day reading until someone came and told her that it was time to go back to practice.

“It wasn’t that I wasn’t good at sports,” she says. “I was actually pretty good, but early on, I was also very interested in education.”

Her mother, being a social worker, found her own way to encourage her daughter’s success. She surrounded her with books and encouraged her to apply for writing and essay awards around the community. She also persuaded her to try out different career experiences through volunteer work and internships. For example, when Carter was in high school and expressed interest in being an accountant because she was good at math, her mom helped her with an after-school internship at a bank to see if it was a good fit. Her mother’s support, “was a combination of practical support, encouragement of passion-driven work, and a message that anything is possible if you work at it,” Carter says.

I think this is it

Finding a path

In high school she took an AP psychology course and realized she loved not only the subject but the whole process of listening to people. “I think this is it,” she thought to herself. It aligned with her mother’s work in social services for one thing but having been influenced by a beloved aunt’s storytelling, she loved the idea of understanding and learning from the narrative of people’s lives (qualitative research would later become an important part of her research methods).

A summer program at the University of Richmond put Carter in contact with “some of the smartest people I’ve ever met,” she says, and she realized that they were applying to impressive colleges. It gave her the first real glimpse of what educational paths might lie ahead.

She and her best friend from the summer program applied to UNC Chapel Hill, and both were admitted. Carter’s father was proud she got in, but from his pragmatic point-of-view, his first response was, “who’s paying for this?” Her mother helped her research scholarships and fill out forms and write scholarship essays every Sunday afternoon. She was eventually awarded a full ride scholarship.

It changed my whole world

Finding a purpose

Although she was sure psychology was her field, it was not until she heard Professor Enrique Neblett speak at UNC that it came into focus for her. He was one of the first Black psychologists she had met, and it blew her mind that he was studying Black people. “I didn’t even know this was a thing,” she says. She went up to him after the talk and asked, “how do I do the work that you do?”

She ended up taking his class, the “Psychology of Black Americans,” and it was during this course that she began talking with members of her community about stress which led to her aha moment about the Black experience. “It changed my whole world,” she says of the course and assignments. She still thought that she would be a practicing clinical psychologist, but with Dr. Neblett’s encouragement, she realized that she could do research that might make a difference in this experience people were having overcoming obstacles to life and longevity.

She applied to a lot of graduate programs, thinking that if she did not get into one, she could always “be my mom” and help people in other ways through social services or the Peace Corps. But she got some acceptances and chose the University of Georgia where she earned her Ph.D. in clinical psychology.

A perfect blend

A research agenda

At UGA she focused on becoming a therapist in the clinical psychology program because she says research lacked the immediate feedback and satisfaction you get in therapy and because many of the Black scholars she met seemed stressed and burned out by their experience in academic spaces.

She continued on that path through her internship at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and post-doc at the Grady Trauma Project. The post-doc position “was a perfect blend” of research and clinical work, she says, which allowed her some feeling of helping individuals while also answering bigger questions and expanding her interest in research, but she could not find a similar permanent position. Then she saw a job at Georgia State University for an interdisciplinary scholar on resiliency in youth and health disparities. It was the closest thing to a match for her she had seen.

She was offered the position, and through it, she now runs her HEART lab with R01 funding from the NIH in which she works to excavate the processes and experiences that negatively affect the health of Black Americans as well as the interventions that can prevent those outcomes. With over 80 peer-reviewed publications and many other presentations and writings, Carter has proven to be a standout researcher after all.

Much of her current work focuses on maternal health inequity among Black and Latina women. In one project, she is investigating how the experience of racism by expectant mothers can become biologically embedded in systems that affect not only the mother but also the fetus. In another, she and colleagues are working to decipher how structural racism, through things like redlining practices, voting restriction laws, and historical lynching and enslavement records in Georgia, affect current levels of maternal death and preterm deliveries.

From personal to professional and back again

Carter’s interest in these issues began in college when she realized how much her family and community was affected by them, and then her “somebody needs to do something” thought became her battle cry as a scholar. Now, it is taking a turn toward the personal again as she and her husband are expecting their first child soon. “Everyone deserves the opportunity for their strengths to shine and to live long and thriving lives,” she says. For her son, and everyone else, she is trying to be one of those doing something to make sure they can.

Story and recent photos by David Pollock

Sierra Carter’s family worked to ensure she had every possible opportunity. Can her research help do the same for others?

A component of having opportunity in life

is the chance to live a long, healthy one.

“Somebody needs to do something,” Sierra Carter thought to herself during her post-doc at the Grady Trauma Project through Emory University. She was seeing a lot of Black people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and it got her thinking more about how the structures of society were not working for them. The thought helped define and shape her scholarly career. But it was not the first time she was alarmed by how the broader systems were affecting Black Americans.

the structures of society were not working for them

Growing up in her small southern Virginia town, the chronic illnesses of family, friends, and community members—and not just among the very old—were often present. “Seeing people you know and love not be able to live long and thriving lives was hard to witness,” she says.

But it was not until she interviewed family and community members for a college class that she started connecting the dots and realized the chronic illnesses and early deaths of people around her was not only a part of the community she grew up in but was also a part of other Black communities as well. It led to a startling realization: Black people tended to die younger than those in many other groups.

Fast forward a few years, and Dr. Carter’s recent lecture entitled, “Black people deserve to grow old: Racial trauma, accelerated aging, and the promotion of health-equity related research,” shows that she is trying to do something about the problem. But the college-aged Carter would have been surprised to know she was heading into a life of scholarly work.

The push for success

They wanted me not to have to work as hard as they did

Until heading off to college at UNC Chapel Hill, just over an hour from the home she shared with her parents and older brother, Carter spent her whole life in the same town, in the same house in Axton, Virginia, near the border with North Carolina. The amount of support she had growing up “was ridiculous,” she says. Her parents, aunts, extended family and others pushed and pulled, sometimes behind the scenes and unknown to her, to make sure she and her brother knew they could be and do whatever they dreamed of. Both her parents attended every parent-teacher conference in her life as one simple example of their support and involvement. “They wanted me not to have to work as hard as they did,” Carter explains.

But that support was also wrapped up with some high expectations. For example, she says, “my parents didn’t believe in missing school.” It did not matter if she was sick or whatever. She went (and ended up with a perfect attendance record).

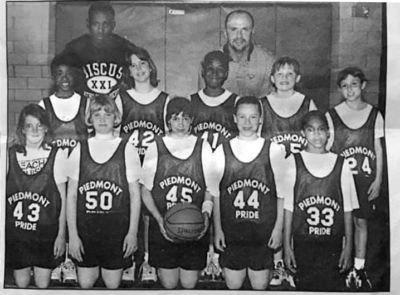

Carter’s father, who coached basketball in recreation and school programs for years, applied his own philosophy to her in that world. He often encouraged her to play in the next, older age group, for instance, and talked about basketball as her path to success—a practical way to pay for college, and then hopefully, into something more than a factory job.

He told Carter and her brother from a young age that, “if you get a scholarship in basketball, I’ll buy you a car,” she says as one of his ways of motivating them to excel.

Sometimes, while her dad was mentoring and coaching the boys and girls at the YMCA on Saturday mornings, some of the older girls would take her away to the library just across the street where she would end up spending the day reading until someone came and told her that it was time to go back to practice.

“It wasn’t that I wasn’t good at sports,” she says. “I was actually pretty good, but early on, I was also very interested in education.”

Her mother, being a social worker, found her own way to encourage her daughter’s success. She surrounded her with books and encouraged her to apply for writing and essay awards around the community. She also persuaded her to try out different career experiences through volunteer work and internships. For example, when Carter was in high school and expressed interest in being an accountant because she was good at math, her mom helped her with an after-school internship at a bank to see if it was a good fit. Her mother’s support, “was a combination of practical support, encouragement of passion-driven work, and a message that anything is possible if you work at it,” Carter says.

Finding a path

In high school she took an AP psychology course and realized she loved not only the subject but the whole process of listening to people. “I think this is it,” she thought to herself. It aligned with her mother’s work in social services for one thing but having been influenced by a beloved aunt’s storytelling, she loved the idea of understanding and learning from the narrative of people’s lives (qualitative research would later become an important part of her research methods).

I think this is it

A summer program at the University of Richmond put Carter in contact with “some of the smartest people I’ve ever met,” she says, and she realized that they were applying to impressive colleges. It gave her the first real glimpse of what educational paths might lie ahead.

She and her best friend from the summer program applied to UNC Chapel Hill, and both were admitted. Carter’s father was proud she got in, but from his pragmatic point-of-view, his first response was, “who’s paying for this?” Her mother helped her research scholarships and fill out forms and write scholarship essays every Sunday afternoon. She was eventually awarded a full ride scholarship.

Finding a purpose

Although she was sure psychology was her field, it was not until she heard Professor Enrique Neblett speak at UNC that it came into focus for her. He was one of the first Black psychologists she had met, and it blew her mind that he was studying Black people. “I didn’t even know this was a thing,” she says. She went up to him after the talk and asked, “how do I do the work that you do?”

It changed my whole world

She ended up taking his class, the “Psychology of Black Americans,” and it was during this course that she began talking with members of her community about stress which led to her aha moment about the Black experience. “It changed my whole world,” she says of the course and assignments. She still thought that she would be a practicing clinical psychologist, but with Dr. Neblett’s encouragement, she realized that she could do research that might make a difference in this experience people were having overcoming obstacles to life and longevity.

She applied to a lot of graduate programs, thinking that if she did not get into one, she could always “be my mom” and help people in other ways through social services or the Peace Corps. But she got some acceptances and chose the University of Georgia where she earned her Ph.D. in clinical psychology.

A research agenda

At UGA she focused on becoming a therapist in the clinical psychology program because she says research lacked the immediate feedback and satisfaction you get in therapy and because many of the Black scholars she met seemed stressed and burned out by their experience in academic spaces.

A perfect blend

She continued on that path through her internship at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and post-doc at the Grady Trauma Project. The post-doc position “was a perfect blend” of research and clinical work, she says, which allowed her some feeling of helping individuals while also answering bigger questions and expanding her interest in research, but she could not find a similar permanent position. Then she saw a job at Georgia State University for an interdisciplinary scholar on resiliency in youth and health disparities. It was the closest thing to a match for her she had seen.

She was offered the position, and through it, she now runs her HEART lab with R01 funding from the NIH in which she works to excavate the processes and experiences that negatively affect the health of Black Americans as well as the interventions that can prevent those outcomes. With over 80 peer-reviewed publications and many other presentations and writings, Carter has proven to be a standout researcher after all.

Much of her current work focuses on maternal health inequity among Black and Latina women. In one project, she is investigating how the experience of racism by expectant mothers can become biologically embedded in systems that affect not only the mother but also the fetus. In another, she and colleagues are working to decipher how structural racism, through things like redlining practices, voting restriction laws, and historical lynching and enslavement records in Georgia, affect current levels of maternal death and preterm deliveries.

From personal to professional and back again

Carter’s interest in these issues began in college when she realized how much her family and community was affected by them, and then her “somebody needs to do something” thought became her battle cry as a scholar. Now, it is taking a turn toward the personal again as she and her husband are expecting their first child soon. “Everyone deserves the opportunity for their strengths to shine and to live long and thriving lives,” she says. For her son, and everyone else, she is trying to be one of those doing something to make sure they can.

Story and recent photos by David Pollock